The Logical Fallacy of the NCAA’s New Hand-Check Rules

Section 5. (Men) Hand-Checking (Impeding the Progress of a Player)

To curtail hand-checking, officials must address it at the beginning of the game, and related personal fouls must be called consistently throughout the game. Some guidelines for officials to use when officiating hand-checking:

- When a defensive player keeps a hand or forearm on an opponent, it is a personal foul.

- When a defensive player puts two hands on an opponent, it is a personal foul.

- When a defensive player continually jabs by extending his arm(s) and placing a hand or forearm on the opponent, it is a personal foul.

- When a defensive player uses an arm bar to impede the progress of a dribbler, it is a personal foul.

That is the official language in the NCAA’s 2012-2013 official men’s basektball rule book. Now, let me show you the official language from the 2013-2014 rule book regarding the same scenario.

Section 5. Hand-Checking (Impeding the Progress of a Player)

To curtail hand-checking, officials must address it at the beginning of the game, and related personal fouls must be called consistently throughout the game. Some guidelines for officials to use when officiating hand-checking:

- When a defensive player keeps a hand or forearm on an opponent, it is a personal foul.

- When a defensive player puts two hands on an opponent, it is a personal foul.

- When a defensive player continually jabs by extending his arm(s) and placing a hand or forearm on the opponent, it is a personal foul.

- When a defensive player uses an arm bar to impede the progress of a dribbler, it is a personal foul.

Notice any changes? The language is identical, but the NCAA did drop a few nuggets elsewhere into the rule book. For example, in the “Major Officiating Concerns” section:

Handchecking

The rules committee is concerned that various types of handchecking on a player with the ball drastically reduces the dribbler’s ability to beat his man to create scoring opportunities. Accordingly, certain guidelines for officiating these plays have been inserted into Rule 10 and officials are instructed to call the fouls as written in the rules.

Freedom of Movement

The rules committee continues to express concern that the rules relating to a player’s ability to move with or without the ball are being neglected by officials resulting in more physical play and less opportunity for scoring. Officials need to refocus their energies on penalizing illegal contact by the defense which prevents players from cutting freely, running their offense and otherwise creating a more free-flowing game.

The NCAA also inserted some of the language from Section 5 into Rule 10 by changing articles 4-7 in order to give officials more information on how to call these fouls inside the rule itself.

Art. 4. The following acts constitute a foul when committed against a player with the ball:

a. Keeping a hand or forearm on an opponent;

b. Putting two hands on an opponent.

c. Continually jabbing an opponent by extending an arm(s) and placing a hand or forearm on the opponent;

d. Using an arm bar to impede the progress of a dribbler.

Art. 5. A player shall not extend the arm(s) fully or partially other than vertically so that freedom of movement of an opponent is hindered when contact with the arm(s) occurs.

Art. 6. A player shall not use the forearm and/or hand to prevent an opponent from attacking the ball during a dribble or when trying for goal.

Art. 7. A player may hold his hand(s) and arm(s) in front of his own face or body for protection and to absorb force from an imminent charge by an opponent.

In reality, there is nothing new here. Hand-checking has always legally been a foul. It was just called less and less over time.

Officials for the NCAA and referee associations have been quoted in support of this change. Curtis Shaw, the coordinator of the venerable officials from the Big 12 Conference among others, has been quoted saying that “physical defense was never part of the game of basketball.” Others in support of this rule emphasis tend to argue that this change gets us back to the “good old days” where basketball was an athletic sport and not a physical one. This will eliminate all of these low scoring dog fights and get us back to the free flowing, high scoring days of old, right?

“Not so fast” as Lee Corso would contend. This conclusion is based on the assumption that all other things are equal in the modern game of basketball, when that is absolutely inaccurate. What has changed so that the defenses of today have evolved into a more physical style of play? Why, the offenses that have become just as physical, of course.

Third law: When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to that of the first body.

These rule changes completely gloss over the fact that defenses have changed in response to the kinds of offensive weapons never before seen in the game of basketball. People like Jay Bilas often harken back to the 1980’s to compare it the modern day perimeter play. He says, “Go back and look at tape of games in the 80’s. You couldn’t go near guys without getting a foul called. Listening to people whine about this is laughable. Move your feet and get out in front.” There is no argument, the way defenses guard today would have been called fouls back then. My only contention is that there is a good reason for the change in style, and it is not simply that coaches have found they can “cheat” or get away with more fouls on defense, and so that is how they are coaching.

Bilas himself has been quoted numerous times saying that there is no question that college athletes today are more skilled and more physical than they were back then. Watch some game film from the 80s. Sure, the dribble-drive was alive and well back then, but the speed and physicality were not the same. There was far more east-west movement as guards surveyed the court. When they did drive it was usually because there was a pretty wide-open lane where they could avoid contact and score. Nowadays, big, physical guards look to drive it right into the teeth of the defense. They lower their shoulders and attack right into the bodies’ of the defenders. Guards that can absorb that contact and score are lauded for their superb body control.

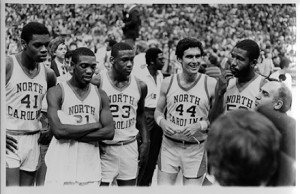

Let me give you another example. Let’s use Michael Jordan, the greatest player of all time, so I can’t be accused of low balling here. Michael Jordan was considered by many to be the greatest athlete of the day when he was at his prime. When he came to college at UNC he weighed 195 lbs on a 6’6″ frame. When he left for the NBA three years later, he weighed the same 195 lbs. He was an above average physical specimen for his position at the time. Some other greats of old at that wing position are Ray Allen (197 lbs), Reggie Miller (185 lbs), Clyde Drexler (210 lbs), George Gervin (180 lbs) and Kobe Bryant (190 lbs). I tried to find their rookie weights as much as possible, but for some of the older players, these weights represent their prime in the NBA. Even so, the average weight for the guys comes to 192 lbs.

Now what about the average weight of the top six incoming wings in the country this season? That comes out to a cool 208 lbs. That means that today’s incoming perimeter players have about 16 lbs of girth on their “golden day” counterparts in this admittedly non-scientific study. And, like I mentioned, we are talking about most of those former greats in their prime in the NBA, not as 18 year old freshmen in college. Today’s elite basketball player is a finely tuned machine by the time they are 18-20 years old, wrought by years of coaching, training and fierce competition from a young age.

That fact is, defenses have become more physical over time because you need that physicality to stop offensive super-athletes that are faster, stronger and more explosive than they ever have been. I am all for more scoring and a free-flowing display of athletic basketball prowess, but as long as perimeter players are lowering their shoulder and driving right at their defenders, defenders are going to need some tactic to slow them down, otherwise they will get blown by every time. Bodying up and the use of the forearm for some leverage has been the tactic of choice recently.

If the offensive player is going to make the decision to initiate contact, the defense initiates some contact right back in an attempt to level the playing field. The guard with ball is making the bet that he can use his superior athleticism and physicality to gain an advantage on the defender, and so, in turn, the defender tries to counter that with his own physical play. Usually one of two things happens. Either the defender is unable to gain leverage and the offensive player gets by him, or, the offensive player’s path to the basket is altered and the defender wins.

Now, there are limits to this. Basketball is still, at its heart, a game played with the feet. Guys still have to go straight up with their hands, they can’t grab the jersey or body of their opponent, they cant check with two hands as a defender. I am all for that type of limitation, but sitting there and trying to tell me that guys will somehow be able to “adjust” to using no upper body leverage against a 225 lb man who has just lowered his shoulder and is trying to get to the rim, by you or through you? It is absurd. There is no adjusting to that. Many times, even if the defender does nothing, the refs are calling fouls because of the contact the offensive player initiated. The only option I see is to open your stance and let the guy with the ball by you so that he can get fouled by your buddy in the paint when he tries to go straight up but is also guilty of physical contact. Who cares that the guy with the ball launched right into his body. That is the way guards are taught to play the game.

I don’t expect the NCAA to try to temper the way athletic guards attack them rim. I just expect them to give defenders a fair chance.

But you don’t need the numbers appreciate these differences. They are clear when you watch the games. Look at this picture of the 1981-82 Tar Heels team featuring a young MJ and compare it to a locker room shot of the Jayhawks from earlier this year…

… not even close.

I think, like most new season emphases, things will lighten up enough by conference play to at least make the games watchable. Even in the game against Louisiana Monroe, there were plenty of times when Mason and Selden used their hands to try to combat the physicality of their opponent without being called for a foul. It is such a natural reaction to the contact that guys are going to do it as long as offensive players are physical with them. These refs can’t rightly foul out the whole team, so we will find a balance. It may just be a little ugly until we do.

489 thoughts on “The Logical Fallacy of the NCAA’s New Hand-Check Rules”